Testing for PPX and TCA: Is it Necessary?

Today’s subject was sparked from a conversation that our sales consultants have fairly regularly. Usually this comes up in the context of us pressing to find out why a facility is using the specific tests that they are using. The answer we get more than any other is some variant of, “it’s just the way we’ve always done it.” If you’ve had any conversations with our sales team, you know they won’t simply let that answer stand alone. It is always our mission to understand the needs of each facility we work with, but sometimes this can entail explaining why some of the thought processes behind those needs might be misguided, outdated, or missing crucial bits of information.

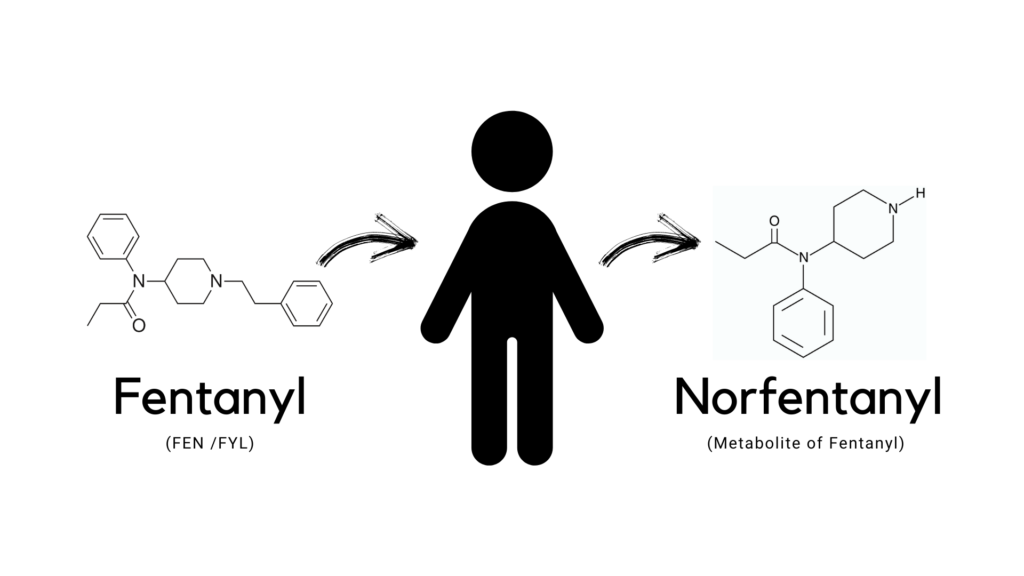

For example, when inquiring why a facility is not testing for Fentanyl, when it is clearly the most concerning drug of abuse, we will often hear the previously mentioned, “it’s just the way we’ve always done it”, or, specific to Fentanyl, “we assumed that this would be detected on our Opiate panel”. This covers all three of the thought processes I described.

However, for this blog post, we are going to focus on the other side of this coin, substances that people have been testing for that may or may not be necessary. Keep in mind, I will never fault anyone for playing it safe and testing for everything that they can, but this doesn’t always work for facilities that need to keep costs down. I always recommend that people find a happy medium, and keeping our clients informed about substances that are of the highest concern at the time is incredibly important in helping such facilities try and find that happy medium.

Today we are going to look at Propoxyphene (PPX) and Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCA) with a nod to a couple of honorable mentions in Barbiturates (BAR) and Phencyclidine (PCP).

First, Propoxyphene, more commonly known by its brand names, Darvon and Darvocet, is a mild Opioid pain reliever. It dates back to 1954 and was developed, like most Opioids, as an attempt to create a non-addictive pain medication. Spoiler alert, it was still addictive! Being that it was a mild Opioid, it did have a slightly lower risk of addiction, but it was neither non-addictive nor totally safe, as such, this medication has been taken off the shelves in the US since 2010. Most other First World countries follow suit shortly thereafter. While it is still prescribed in other countries, albeit infrequently, it is not completely gone from the world. However, with many more commonly prescribed, and therefore more readily available Opioids, I have never in my 20+ years heard of a Propoxyphene positive result, nor any facilities having concerns with its misuse.

Next up is Tricyclic Antidepressants. Tricyclic Antidepressants are a class of antidepressants characterized by their chemical structure, which contains three rings of atoms. TCAs were also developed in the early 1950s during the early days of psychopharmacology (psychopharmacology being medications to treat mental disorders). TCAs are typically classified as, “mood elevators”, and the most commonly known is probably Elavil (Amitriptyline). These medications have not been pulled from shelves like Propoxyphene, but they are rarely prescribed these days in favor of the more modern class of antidepressants, such as SSRIs (Prozac and Celexa), SNRIs (Cymbalta and Effexor), and NRIs (Wellbutrin). Near obscurity aside, according to the US government classification of psychiatric medications, “TCAs are non-abusable”. While in slightly higher demand than testing for Propoxyphene, TCAs can be a good place to cut back on if you are trying to keep costs down.

Honorable mentions: Barbiturates (BAR) and Phencyclidine (PCP).

Please do not interpret this as my advising not to bother, or that you don’t need to test for these, but I wanted to include this in an attempt to point out how uncommon these substances have become in terms of drugs of abuse. Barbiturates have long since been replaced in most cases with Benzodiazepines (especially for sedation). However, we do see a small number of prescription medications that contain them. Fioricet, for example, is a common medication prescribed for migraines.

If you are testing BAR, I am going to guess that you probably have never seen a positive result. To a lesser extent than BAR is PCP. This dissociative anesthetic was used medically from 1956 to 1965 (1978 for veterinary medicine), until discontinued due to high rates of negative side effects. We typically see the better tolerated, Ketamine (KET), being used for anesthetic purposes in its place. While we do sometimes hear about geographic pockets of the country where this substance pops up from time to time, it is not nearly as widespread as it once was.

In summary, do not take this article as the final word on what tests are best for you or your facility to use, but take this to open up a conversation about whether or not, what you are testing for is really what you need to test for, or if it is just the way you’ve always done things.